An acquaintance once asked me if I could read out loud an excerpt from a poem written in Farsi. She had been intrigued by the language and its 13th century poets, and I suppose she wanted to hear a native speaker recite it. She was hopeful I’d be able to deliver the authenticity she craved.

I held the book in my hands and skimmed through the pages. For some reason I felt I could accomplish this task if I really put my mind to it. The letters, a beautiful cascade of curves and dots, looked familiar enough. I knew if given enough time to study it by myself, I would be able to read it and even relay its infinite wisdom and beauty to the curious and interested. But after an awkward few minutes of silence, I admitted to her I was basically illiterate in my own native language – well, as far as reading and writing goes.

The conversation went like it always did in situations like these. A long explanation as to why this was the case and how being an immigrant had posed all kinds of linguistic and cultural challenges in my life. Explaining to her the dreaded state of inbetweenness so commonly experienced by immigrants such as myself felt like an involuntary yet necessary act of vulnerability in that moment.

It all brought me back to Wednesdays after school, being in a classroom with other kids that spoke Farsi. Sitting in the front row but dreading the thought of getting called to recite something out loud. We were all there because our parents wanted us to have some remnant of the heritage now thousands of miles behind us, one we can’t even go back to visit anymore. Nonetheless, as outsiders in a land completely foreign to us, it was important to establish a home, at least within ourselves.

There were certainly kids who had the proclivity and desire to absorb what was being taught, but for others it felt more like a burden than a bridge to our heritage. For me, there was a much stronger pull towards the dominant culture that it overshadowed the importance of preserving my own roots. My childlike reasoning was: what’s the use in holding on to the past?

Now, a few decades later, as life experience has equipped me with a more nuanced understanding of my current predicament, it has dawned on me that this process of integration has come at a personal cost. Beyond the obvious notion that my facial features, skin color, and hair texture will always set me apart from the native population and that no amount of assimilation will make up for it, comes a different kind of reckoning: there’s a good chance that I will always find myself in this state of neither here nor there.

Many of the 1.5 generation immigrants I know have had to struggle with their identities one way or another. There is a shared but concealed experience of loss that has to do with identity and culture. Something intangible, yet very much real. Most of us arrive at the finish line, (i.e. diplomas in hand or comfortably positioned in the jobs we worked so hard to get) only to realize that there are no rewards for having sacrificed parts of ourselves along the way. I sometimes think if I had only paid attention in our native language classes and taken initiative to read more, perhaps I’d spend much less time in this state of inbetweenness.

What’s unique about first language attrition in the case of immigrants such as myself is that erasure of this part of my identity is not considered much of a loss in the grand scheme of things. Sure, it’s a shame I can’t read Rumi in Farsi, but in its place, I’m fluent in two other major languages that will surely guarantee social integration and even upward mobility. Losing connection to a culture that, by western standards at least, is backwards and primitive is worth it, if for nothing else, then for the sake of assimilation.

Acculturation in a Nutshell

In conversations around refugee integration, we often hear that the root of all problems stems from a failure to assimilate adequately. This explanation is fairly superficial, and disregards the fact that integration is multifaceted process that is anything but straightforward. Assimilation is only one way of acculturating to a new society, but it has a negative connotations, as we can see from its definition:

The process of assimilating involves taking on the traits of the dominant culture to such a degree that the assimilating group becomes socially indistinguishable from other members of the society.

– The encyclopedia Britannica

This understanding of assimilation is quite extreme, yet it is the standard to which many immigrants are held to. The idea that diverse groups of people should seamlessly blend into larger society so that their presence is neither seen nor heard is extremely racially charged and quite the opposite of the melting pot analogy we are used to romanticizing.

Not to mention that it is also quite impossible and undesirable for many to “take on the traits” that make them indistinguishable from the larger population. This is only desirably if the goal is to maintain as homogeneous a population as possible, but then we’d be treading dangerously close to the radical ideals of fascism.

In addition to being an unrealistic yardstick to measure social integration, assimilation does not yield the best results according to research either (Berry et al., 2010). Thankfully, there are other strategies of acculturation that are more fruitful.

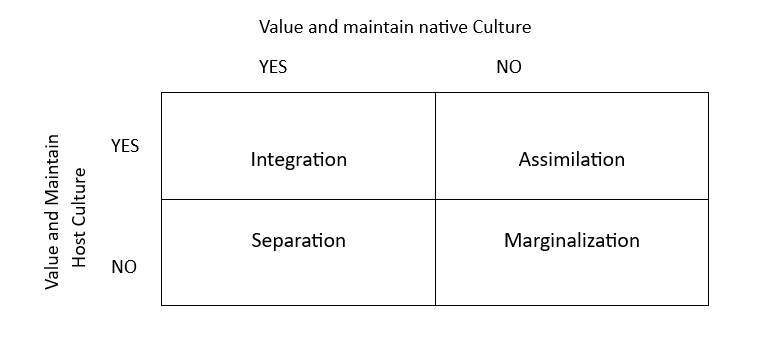

The acculturation model proposed by Berry (2001) offers four different ways a person can integrate into society. There is assimilation, separation, marginalization and integration. Since assimilation is referred to a situation where the cultural norms of the dominant culture are adopted over one’s original culture, it is likely to result in cultural loss and even cause psychological problems such as anxiety or depression (Berry et al., 2010). On the other side of the spectrum, separation occurs when a person rejects the dominant culture in an effort to preserve their original culture. Integration, by and large, is the preferred strategy since it promotes the maintenance of one’s culture of origin while adopting the norms of the host culture. This strategy is likely to cause the least amount of psychological issues mentioned previously. And lastly, marginalization occurs when there is little to no interest in maintaining one’s culture of origin nor seeking involvement with larger society.

What Influences How a Person Chooses to Integrate?

In a study regarding the acculturation of immigrant youth (2010) done by Berry et al., the researchers collected data from 7,997 adolescents from the ages 13 to 18, across 13 different countries. The group included immigrant adolescents as well as national youth, and the goal was to address three key issues:

- How do immigrant youth live within and between two cultures?

- How well (in personal, social, and academic areas of their lives) do immigrant youth deal with their intercultural situation?

- Are there patterns of relationships between how adolescents engage in their intercultural relations and how well they adapt?

Based on the data collected, the participants were categorized to four different acculturation profiles: a national profile (18,7%) an ethnic profile (22,5%), an integration profile (36,5%) and a diffuse profile (22,4%). The first group consisted of youth that favored assimilation, scoring high on having a national identity and very low on ethnic identity. The ethnic profile had adolescents that showed a clear preference towards their own cultural heritage and little involvement with their national peers. The third profile was the largest category, including adolescents that showed positive attitudes towards integration, and had a balanced approach to both ethnic and national peer contacts, involvement with larger society and greater adaptability in terms of identity. Lastly, the diffuse profile consisted of those who didn’t neatly fit into the previous categories and had inconsistent patterns regarding the variables included in the questionnaire. This is thought to imply uncertainty about one’s place in society, which could either mean that they do not yet have the needed skills to form meaningful contacts or that there is a lack of commitment to do so.

The thing that stands out is that while the integration profile was the most frequently occurring one out of all four, the ethnic profile combined with the diffuse profile make up a large percentage of the sample size. That is to say, for almost half of the participants, integration has posed notable challenges. There is also another factor that isn’t considered in the research: how a given ethnic culture is perceived by larger society. More specifically, is there a difference between the acculturation choice of someone who is from Poland vs. someone who’s from Iraq? And how much of that is influenced by outside forces versus personal convictions? The differences in attitude and treatment of ethnic groups can showcase not only national preferences (preferring one ethnic group over another), but also the degree of discrimination a person faces which can then influence how they adapt to their environment.

In view of this, the ‘diffuse’ group most likely includes youth that have received mixed signals from both cultures and therefor have a hard time adapting to either one. While the researchers concede that societal attitudes towards immigrants (incl. discrimination) and the policies of the host country play a significant role in the acculturation strategy one chooses, the success rate for one group of immigrants to integrate versus the other is important to study further. There was, however, a comparison made between Muslims and Judeo-Christians in the data, which revealed that integration was the preferred choice among Judeo-Christians while Muslim representation was dominant within the ethnic profile. While it is understandable that strong contrasts between value systems can pose serious challenges to smooth integration, if we can mitigate other factors that hinder integration, such as inequality in educational and career opportunities, we will find that differing value systems are not as insurmountable as we might think.

Other factors such as age, gender, duration of residency, parents’ occupational status, experiences with discrimination as well as the ethnic composition of the neighborhood were also important in how the youth adapted. For instance, girls were more inclined towards integration and having better academic success compared to boys. The ones in the national profile had parents with a slightly higher socioeconomic status, they lived in areas that were less ethnically diverse, and had a higher proficiency in the national language.

To assess how well immigrant youth were adapting in matters regarding their social and personal lives, the researchers looked at psychological adaptation and sociocultural adaptation (developed by Ward, 1996), and found that there were clear distinctions between the profiles in terms of personal well-being (psychological) and ability to manage daily life (sociocultural). Those who had an integration profile, scored high on both psychological and sociocultural adaptation. In other words, adolescents that were oriented towards integration fared well when it came to their mental health, school adjustment, self-esteem and life-satisfaction. Conversely, the diffuse group had the weakest outcomes in these same areas. Notably, those in the national profile ranked relatively low on psychological adaptation. This is likely the result of not having as strong of a connection to one’s own cultural heritage, which can then lead to issues with identity and self-esteem.

Implications for Policy Making

It’s clear to see that while integration is important for the overall well-being and success of individuals, struggles with identity and intercultural adaptation are central issues. In light of this information, several assertions can be made. The process of integration is more complex than often recognized, and assimilation is not the preferred strategy for adapting to a new society due to its many drawbacks. The findings of the study are very well understood by experts in the field, yet misrepresented by policy makers in public conversations around immigrant acculturation.

The popular idea that, failure to integrate is solely responsible for the rise in anti-immigrant sentiments, needs to be challenged because even those who adapt seamlessly into their new host countries, are faced with prejudice. It’s actually common for immigrants and refugees to be encouraged to shed their former identities in exchange for acceptance, only to realize that the barrier to entry is strongly tied to things such as appearance, language use, and other markers of identity linked to social class. Many of us have been in situations where even a high level of language proficiency isn’t enough to grant us access to certain spaces. In other words, there’s an obvious racial bias that directs these conversations regardless of how logically sound the arguments are made out to be. As seen from the study above, even the data supports the idea that adopting the host country’s value system at the expense of one’s own inherited values is neither realistic nor advisable. Therefore, it’s time to contest the populist assertion that assimilation necessarily leads to better acceptance and success for immigrants.

From where I’m standing, it’s obvious that being an immigrant adds additional layers to the common human experience known as judging a book by its cover. And so with these additional layers such as having a darker complexion, different facial features and hair texture, or a distinct accent, there are inevitably more barriers to cross when it comes to social integration.

So what does this all mean in terms of policy making, especially in this current political climate? I’ve written all this in an effort to make the following point: It matters greatly if immigrants, especially the youth, feel disconnected from their heritage and themselves. It matters if we are seen as nothing more than working bodies to serve the economy and discarded and dehumanized the moment we become a net negative. It matters because seeing a considerable segment of the population as liabilities and problems to fix, will lead to policy making that is not only unjust but also dehumanizing.

The goal of integration should not be to replace a person’s identity but to promote an atmosphere of cohesion, and to cultivate an individual according to their unique attributes while considering their starting point. We ought to be wary of rhetoric that aims to create division by implying that most social issues are a direct cause of unsuccessful integration. It is essential to recognize that an immigrant with a fragmented identity and a negative self-image reflects a damaged psyche that can, at worst, fuel the very social issues that populists exploit to create division among us. And what can damage a person’s identity and sense of belonging more powerfully than an environment that rejects their core being?

Perhaps the essence of this entire article boils down to this simple, yet painful truth: As immigrants, we are constantly giving up parts of ourselves whether to appease others or just out of necessity. We are faced with choices that the larger population is totally oblivious about. For some of us, the wheel has to be re-invented from scratch especially when we become parents. How do we speak to our children—in a language that feels like home or one that makes them belong? How do we hold on to our cultural roots without being labeled as outsiders? How do we protect our children from the prejudice we’ve faced, without burdening them with our fears? And can we ever feel truly accepted in a place that constantly reminds us of our foreignness?